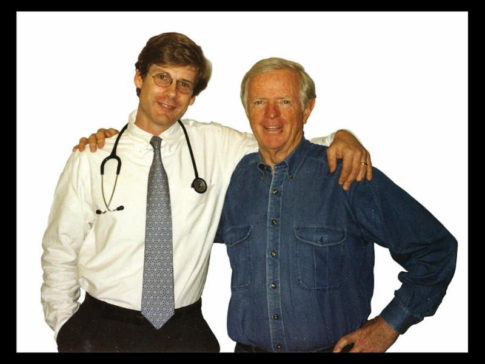

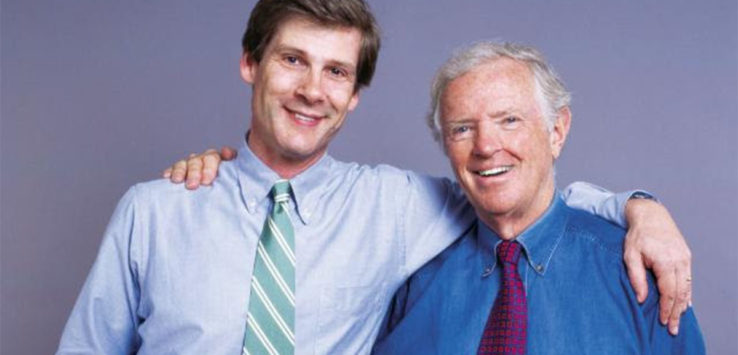

Many of you will have heard the dreadful news that Harry died, of prostate cancer, on Friday March 10th at the age of 58. Awful damned sad and still all-but-impossible to believe. There he is in the pic above, just a dozen years ago, in the photo for the back cover of our then-new book, Younger Next Year. At that point, I had known him for about two years. It already felt as if we had been close all our lives.

In a sense we had been. We’d both grown up in nice, sea-port towns, north of Boston… Harry in Beverly and me in Marblehead. We used to stand in his examining room where he had a nautical chart of the area…point out that we lived only five miles (and 24 years) apart. We both grew up in big, ocean-front houses in comfortable families, his famous as well. And we both went to tiny Shore Country Day School, in Beverly. (In a draft of the book, I told a story about a kid in my first grade class in 1940 who famously “didn’t care” and used his real, first name. Harry happened to show a draft to his mother who asked him if I were referring to so-and-so in that chapter. Harry asked me and, yeah, I was. Well, she said, the little boy had died but we should change the name for his mother’s sake, a woman she knew well. Small world, man; small world.)

Harry went to Groton, I went to Exeter. I dutifully went on to Harvard and Harry, rebelliously, went to Penn. But those were modest differences: basically, Harry and I had known each other, and shared deep, New England notions of behavior, integrity and skepticism-in-thought, long before we met. When we did meet, we fit each other as easily and comfortably as a glove your hand. More rarely, we liked each other at once and became deep friends in a remarkably short time. Dunno how Harry would “rank” me in that pantheon, but he was one of a tiny handful of people to whom I was closest in this life. And it was a privilege, believe me. He used it sparingly, but Harry had a lovely gift for friendship. The world was a warm place when Harry Lodge was your close pal.

We not only came from the same neck of the woods, we dressed similarly, too, which is pathetic. Harry’s taste was even worse than mine, which is saying a lot. That’s my tie he’s wearing in the photo; his were just too awful to use. I once had a secretary who said I wore my clothes as if I hated them. Harry wore his clothes as if he simply didn’t notice, which he didn’t. Laura Yorke, his true love and partner – and the brilliant agent who helped us so much with organizing and then selling the book – once gave him a very fancy sweater. Harry knew it was expensive and tried to be appreciative but still said, puzzled: “But I already have a sweater.” He saw food in the same light. Dragging him to a fancy restaurant was (a) hard and (b) a waste. He just didn’t care. He was always after me to eat and drink less. I generally worked hard to follow his advice – which was superb. But in this one area I mostly ignored him because I thought he was an idiot about pleasure, an area about which I knew a lot.

Harry was not an idiot about all pleasures. He took deep pleasure – and returned it – in being father to two absolutely terrific girls, Madeleine and Samantha, and he was superb at it. Lucky father, lucky girls. (see their recent remarks on Facebook, if you have a chance.) When they went to boarding schools up in the Berkshires, near Hilary’s and my big, Victorian house, he stayed with us all the time. Eventually he insisted on renting a wing of our house (ridiculous) where he and the girls stayed, weekends, for a couple of years. Two of the happiest years of Hilary’s and my life.

During part of that time, we also had a very different pal staying with us, sometimes: Walter Robinson, a retired Boston Homicide detective. Walter was a brilliant, much decorated cop and, by the way, a superb shot, a gift which he had had occasion to use. Harry and I came from broadly similar social backgrounds; Walter and Harry did not. Walter – smart, funny and utterly charming – grew up in “the projects” in Charleston, an area where kids stand a 50-50 chance of becoming a cop or a thief. Mercifully, Walter became a cop.

Walter and Harry did not sound as if they came from the same continent, let alone the same town, but they got along nicely. Still, Harry knew Walter’s history and viewed him with a certain alarm. By old habit, Walter always locked himself into our house at night and routinely fell asleep, watching the Red Sox on TV. Harry often had to wake him up to get in. Mildly concerned at getting shot, he’d cry: “Walter, it’ s me, Harry. I come in peace!” Harry also enriched our lives in those years by bringing his enormous Bernese Mountain dog, Bella, to the house (I may have the breed wrong but I sure remember the dog; she was about the size of a Volkswagon, slobbery and very sweet. Harry’s idea was that she would protect the girls; I think that was misplaced.) Olive, our tiny Havanese, got along with the giant, Bella as serenely as Harry got on with Walter. Those were cozy years, man. Very cozy years. Hilary and I cherish them still. We miss the girls a lot. Hell, we even miss Bella. Some.

Harry and I did a lot together in those years and after. Biked a lot in the Berkshires and the City. We did a 75 mile spin around the New York boroughs, not long ago. Skied a lot (down-hill and cross country, east and west) and spent time on my cruising sailboat, in Maine and elsewhere. We never rowed together for some reason, but everything else. Harry had rowed some in school, as had I, and I tried to persuade him to do The Head Of the Charles with me, without success. Still, it was Harry who had that wonderful rower’s build, and I did not. Pity. As the book says, I was in better shape when we met than most of Harry’s patients but I became an absolute hound for exercise, afterwards. I had more time for it than Harry, so he and I could ski and bike comfortably together, at about the same clip. Neither of us were amazing athletes, by the way, but that was never the point. We did it and had major fun, and it worked. Just the way the book promised. A good solid miracle.

Harry was wonderful, wonderful company. He was perhaps the smartest guy I’ve ever known (and I’ve known a few). He knew and cared about everything. And he had this lovely, “relating” mind. More than anything, he was a scientist (and a polymath), but he did not have the usual, scientist’s way of thinking: one-two, one-two etc ’til you get it. He could do that but broad connections and similarities occurred to him too. And to follow him on those great leaps was a joy. He could also talk comprehensibly to a reasonably bright layman like me. He said it was because of a lifetime of being an Internist and having to explain complex medical stuff to his patients. Whatever, he had a real flair for it. Actually, serious trial lawyers have at least a related skill: they have to learn very complex topics in tremendous depth then retell the story, accurately but persuasively, to a bright but very busy person (the judge) in short compass. That shared gift was a huge help when it came time to write the book.

A word about the book. I’d had the original but very rough idea… all I really had was the notion of aiming at Baby Boomers (who eventually made it a cult book) and a shallow understanding of “squaring the curve” of aging – being roughly the same man or woman at 80 as you had been at 50 – mostly with exercise. It was totally clear from the outset that Harry would be the brains of the book. My original premise – when I was trying to persuade him to do it – was that it was not going to eat up his life (a lie, it turns out). We would spend a fair amount of time together, on weekends and such, while Harry educated me. A university of one. Then I’d write the sucker, which would take most of the time. (I still have the original letter I sent to him, saying how all this would work, how easy it would be for him, what good it would do and what a ton of money we’d make.) Then someone – probably Laura – came up with the notion of swapping chapters, me as patient and Harry as doc. I’d still do the lion’s share of the writing. But then poor Harry got into it and just couldn’t help himself. He really cared… we both did. And we both worked like lunatics, for about a year. Pretty soon, he was doing all his own writing, and it was very good indeed. You have no idea how rare that is. One sad “advantage” we had in those days was that Harry got separated – not an easy time in his life – so he had a lot more time than he’d anticipated. It all went right into the book, about which he was increasingly passionate.

The process of writing the book together was an unmixed pleasure, which is rare, I’m told. Most co-authors are at each other’s throats in ten days. The old industry wheeze is that they have to have two limos for the book tour because the co-authors can’t be in the same car together. Harry and I were the exact opposite. We cherished each other’s company, and we worked together as easily and smoothly as one could possibly hope. On the very rare occasions when we had trouble deciding which way to go, Laura was a wonderful (and wonderfully fair) arbitrator. This despite the fact that she was falling in love with Harry during that time. At one point I worried (lawyer-like) that they would “gang up” on me on stuff. Not a bit of it: Laura was utterly fair (and smart) in her recommendations to us. Some were surprised that the book started out with two chapters from me: that was Laura’s notion, just to give you an idea.

More about Laura: it is impossible to overstate her contribution, especially in the early days. Harry and I knew nothing about books. Laura had been in the business for a long time and knew everything. Since we were unknowns, she told us, Harry and I had to have a long “Proposal” to put in front of publishers. Laura had everything to do with creating that document (a hundred pages, it turns out, including a bunch of sample chapters). Once we sold the book, we were similarly blessed in our editor, Susie Bolotin, at Workman. A giant. A rather short giant, but a giant withal. She has been my editor ever since, and it’s been a blessing.

Back to Harry and me. Mostly, we enjoyed each other’s company tremendously and thought similarly, during the writing process and after. Lord knows our training was different but we had each gone through a species of rigorous, intellectual training, we knew how to think and how to work. We both had a profound commitment to making the book true and we shared a skeptical, intellectual tradition. Harry had to teach me virtually everything but it was surprisingly easier than you’d think. And way more fun. One of the best years of my life and – I speculate – probably one of his too. The whole thing was astonishingly easy.

Harry was good about going on TV and on the road to promote the book – and we had fun, going to all the big U.S. cities and to such unlikely spots as Dublin (with Laura and Hilary). But his appetite for it was not as robust as mine. Also, he had a deep commitment to and took a deep pleasure in the practice of medicine and in running the big practice which he had created. He also did a ton of very serious and responsible work for Columbia Medical School which resulted in his winning a slew of honors. Including being named a full professor (he was the Robert Burch Family Professor of Medicine at the Columbia University Medical Center) which is extremely rare for a practicing doctor. I used to beg him to do more outside stuff – told him he would be saving and changing lives wholesale, instead of one at a time. He didn’t disagree with the notion but he had his life, his “day job” and he loved it. Honored it. And, let us be candid: he was, unmistakably, one of the very best doctors in the country. He had an astonishing practice and it was profoundly nourishing to him. Also, frankly, he wasn’t quite the type to put himself out there as a public doc. I think he thought that was a little undignified, a little un-professional. I passionately disagreed but never persuaded him. As a result, we spent less time together after the girls were out of those schools and I turned increasingly to speaking and other books (for which he always had time, including my fiction of which he was an insightful and deeply appreciative fan). But we continued to be very close indeed.

Any note like this has to skip a ton of stuff but one thing has to be added: Harry was one of the funniest men I’ve ever known. I don’t mean one of the people who “get” other people’s wit; he was funny in his own right. His wit was bone-dry, cracklingly smart and great fun. Might have been a bit edgy for some, but Hilly and I loved it. He said stuff that you vaguely thought of writing down but didn’t so I can ‘t give you examples. I can only say that – just as surely as he was one of the smartest people I’ve known – he was one of the funniest.

We are not going to get sloppy here but let me do this last thing. One of the three legs of our book is the importance of the “limbic” or emotional life. Caring, connecting and commitment was always as important as exercise or food. He meant it, he knew it and he lived it. As I say, he was a wonderful parent and a splendid friend. He was not profligate with his friendship: he was one of those guys for whom friendship is easy…everyone liked him and wanted to be with him. But he set a huge store by his privacy and his time alone to read, think and write. He really did live a life of the mind to a surprising extent, for a guy who did so much in the real world. His intellect shows in our book. We deliberately kept it as light as a feather. But, make no mistake, it is a smart book, under the surface. Lots of people re-read it every year as a motivator, and find new stuff every time. That was mostly Harry.

Back to friendship, for the lucky few who were his friends, he was a river. A warm river, too. And because he was so damn big, he was a huge presence in your life, even if you weren’t seeing him every week. A huge, loving, and thoughtful presence, all the time. As I try to comfort myself at his loss, I think how incredibly lucky I was to make a friend like that at the age of, say, 67 and to have him for some fifteen years. Lucky. Very very lucky.

I am sorry to say that Harry and I were both atheists (too bad, you could say), so I don’t think I’m going to see him in the Sweet By and By (if we’re wrong about that, excellent). But that’s okay. His presence and importance and sheer magnitude were such that all of us who were close to him will have him with us in important ways for the rest of our lives. And one of the interesting things about our little book – and I hear this all the time – is that a lot of people who did not actually know him at all feel as if they knew both of us pretty well. And that will go on for a while. We talked often about death, over the years and long before its dreadful appearance in his life. He was wonderfully serene about it. And that continued to be true when his life took this awful turn. Strong guy, and brave.

I suppose the question may arise: doesn’t his premature death undercut the premise of the book? No, not for one minute. We always said that the life-style we were promoting – and which Harry followed carefully – would reduce the risk of death from cancers and heart disease, among other things, by half, but not entirely. You could catch a lousy break, “ski into a tree” or “grow a tangerine in your brain pan,” as the book puts it. But your odds – and your quality of life – were radically improved. That is his legacy and it is absolutely true, as a good many thousands can attest. Including me.

Here is a wryly amusing story from last weekend. I had just learned from Laura that Harry did not have long. Hilly and I were flying out to Colorado for a long, work/ski stay. The day after we heard from Laura, I was up early, working. And then went to get my skis out of the bag… maybe take a couple of runs. I felt funny. Very funny. At my tender age, I have the wit to take such a thing seriously and I called Hilly, said we were going to the hospital. Along the way, I felt much, much worse. We called 911 and I was put in an ambulance with the flashing lights and all that. A terrific local doctor saw me at once and said, alas, I was having a heart attack. We were going to do an internal heart scan and then, presumably, put stents where the blockage occurred.

Here’s the nice part: a little while later the doc says, Good news! No heart attack, no stents. Quite the contrary, your heart veins etc are in remarkably good shape. Your risk of ever having a heart attack are “very, very, very remote.” That’s a quote; son of a gun. Wonderful. But why are we here? Oh, says the super-doc. Stress. Very common in the recently bereaved. And very temporary (I was giving a speech in San Diego two days later). Not to worry. It’s called “the Widow’s Broken Heart, It’s because of your friend, Harry.” Ah.

So Harry’s terminal illness broke my heart. But only for a little while. And the lifetime of habits he gave me created those excellent veins in the heart and made me more or less immune to heart disease. That seems fair.

Okay, the sappy part. I thought Harry really did lead an Heroic life. A practical life, to be sure, but an heroic life as well. He genuinely wanted to do the best thing he could with his amazing gifts. And his gifts, ultimately, were Bringing Light. Light of knowledge, light of friendship, light of love. I loved him profoundly, and am going to miss absolutely everything about him. But mostly, I am going to miss the light.

-Chris

An obituary has appeared in The Times. You can turn to that for other details.

MEMORIAL SERVICES will be held at the ALL SOULS CHURCH, 1157 Lexington Avenue, at Noon on Monday, April 10, 2017. In lieu of flowers, contributions may be made to:

THE PRIMARY CARE EDUCATION CENTER,

Columbia University Medical Center

c/o Carolyn Hastings

516 West 168th St. 3rd floor

New York, N.Y. 10032

Oh Chris…I am so sad to read about the death of Harry Lodge. The writing about your friendship and the making of the book “Younger Next Year” , touched me deeply. When You wrote about your broken heart tears came to my eyes. Obviously I never met the man but I feel I know him from your writing and from the many re-readings of the book “Younger Next Year”. When I first read about his passing I immediately remembered reading in the book that even if I did all the stuff you wrote about something could happen and I could die. I think you said it might just be bad luck or something like that. So I figured that’s what happened to Harry.

About your atheist believe or un-believe I have a question for you. If you had to choose between goodness or something bad which would you choose? If you say goodness then I’m sorry to say you are not an atheist, because you see God is All goodness. I don’t know too many people who given the choice would choose something bad over goodness. I pray you find your way to God. He is the Only one who can give us hope.

Thanks for all of your writings and God bless you,

Ines